Local Planning & Finance

TOOL 1

Area or Specific Plans

Area and specific plans can help streamline development activity, protect industrial lands from conversion to other non-industrial related uses, and concentrate planning efforts to create a functional and well-designed industrial district. By establishing clear standards for accepted uses and design and frontloading environmental review processes, area or specific plans can also help incentivize new industrial investment. When used in conjunction with transportation planning or district-based financing tools, area and specific plans can help create a supportive environment for industrial businesses to thrive. The clarity and flexibility provided by area and specific plans can also enable a community’s economy to adapt and evolve over time, because building uses and tenants can change easily as long as new occupants comply with the area’s standards.

Both area and specific plans are targeted land use plans for a defined geographic area that provide a cohesive land use vision, design standards, and broader community goals for programs such as work force development, environmental sustainability, or supporting middle wage jobs for the parcels within that area. These plans typically integrate or address infrastructure improvements necessary to support the anticipated preferred land use activity. Both types of plans are also flexible in the degree of specificity they provide. However, while specific plans have to meet a core set of criteria as defined by state statute, area plans are not directly defined in state law.

Specific plans must include the following components, according to Section 65451 of the Government Code:

- Land uses, including open space within the area;

- Transportation, sewer, water, storm drainage, solid waste, energy, and other infrastructure facilities that would be located in the area;

- Development standards;

- An implementation strategy for financing and public programs to accomplish the specific plan goals;

- Description of the relationship between the specific plan and the general plan.

In contrast, area plans are not specifically defined by state statute. They have the following attributes and differences with specific plans:

- Area plans are typically adopted as a general plan amendment and are implemented by local land use ordinances

- Area plans can be adopted within the context of the General Plan as a special district, or can be adopted as a separate document.

- Area plans provide further refinement to the policies of the general plan for the designated area but are not as detailed as specific plans and often lack a focus on detailed implementation, as required in specific plans.

The two types of plans also differ in their requirements for environmental review. Specific plans require the completion of an environmental review process. Area plans do not necessarily require the completion of environmental review but could include one. The advantage of completing the CEQA process as part of the area or specific plan process is that if a programmatic environmental impact report (EIR) is certified, it establishes an environmental review precedent that can later be used to streamline environmental review for individual development projects. Proactive environmental review can save considerable time and cost for these projects and provides a significant incentive for developers.

To prepare and adopt a specific plan, communities must include public engagement, review existing conditions, and determine the long-goals and objective for the area’s future growth. All of these steps are useful to clearly define the intended role industrial lands can and should play in the future of a community.

In order to use area and specific plans effectively, communities should consider taking the following steps:

- Adopt clear goals for how an area or specific plan will be used to support industrial activities. Provide appropriate buffers and transitions with residential or other non-industrial areas and institute protection from conversions if the industrial properties are at significant risk of alternative uses.

- Use the planning efforts to identify future transportation and infrastructure needs and present strategies for delivering these improvements. Involve utility districts early in this process to ensure that any projected changes to demand power, water, and sewer treatment will be met with adequate supply.

- If possible, incorporate environmental impact reports into area plans, even though they are not required; this can help pave the way for streamlined development in the future.

- Seek to provide clear standards and use definitions in zoning and design guidelines—all of the recommendations from the zoning toolkit apply to area and specific plans as well.

Case Study #1 – West Oakland Specific Plan

The West Oakland Specific Plan was created in 2014 to provide a development framework for vacant and underutilized parcels in the West Oakland area. The plan includes a land use framework, transportation and infrastructure investments, a chapter on social equity that addresses both affordable housing and equitable economic development, and implementation strategies. At the time of adoption, just 17 percent of the specific plan area was used for commercial or industrial uses. The plan identified 37 opportunity sites in these areas and proposed transportation and infrastructure improvements to activate those sites.

What to Look At

- Section 4.1: The specific plan offers an example of reconciling potentially incompatible uses within a plan area. While the plan primarily focuses on commercial and industrial development, 60 percent of the area in 2014 was dedicated to residential uses. The plan focuses on preserving the industrial activities that can coexist with these uses and redirects heavier industrial activity to adjacent areas. Section 4.1 discusses the City’s policies for preserving industrial areas through the specific plan, and page 4-90 provides strategies for limiting industrial conversions.

Source: City of Oakland, 2014 - Section 11.2: One of the distinguishing factors of specific plans is their focus on implementation. Section 11.2 provides an implementation matrix for the plan, detailing strategies for fostering revitalization, updating land uses, and infrastructure enhancements to achieve the plan’s vision.

Case Study #2 – West Berkeley Area Plan

The West Berkeley Area Plan focuses on cultivating a mix of industrial, office, arts, residential, retail, and institutional activities in the West Berkeley Area. The plan was adopted in 1993, revised in 1999, and revised again in 2011. What to Look At

What to Look At

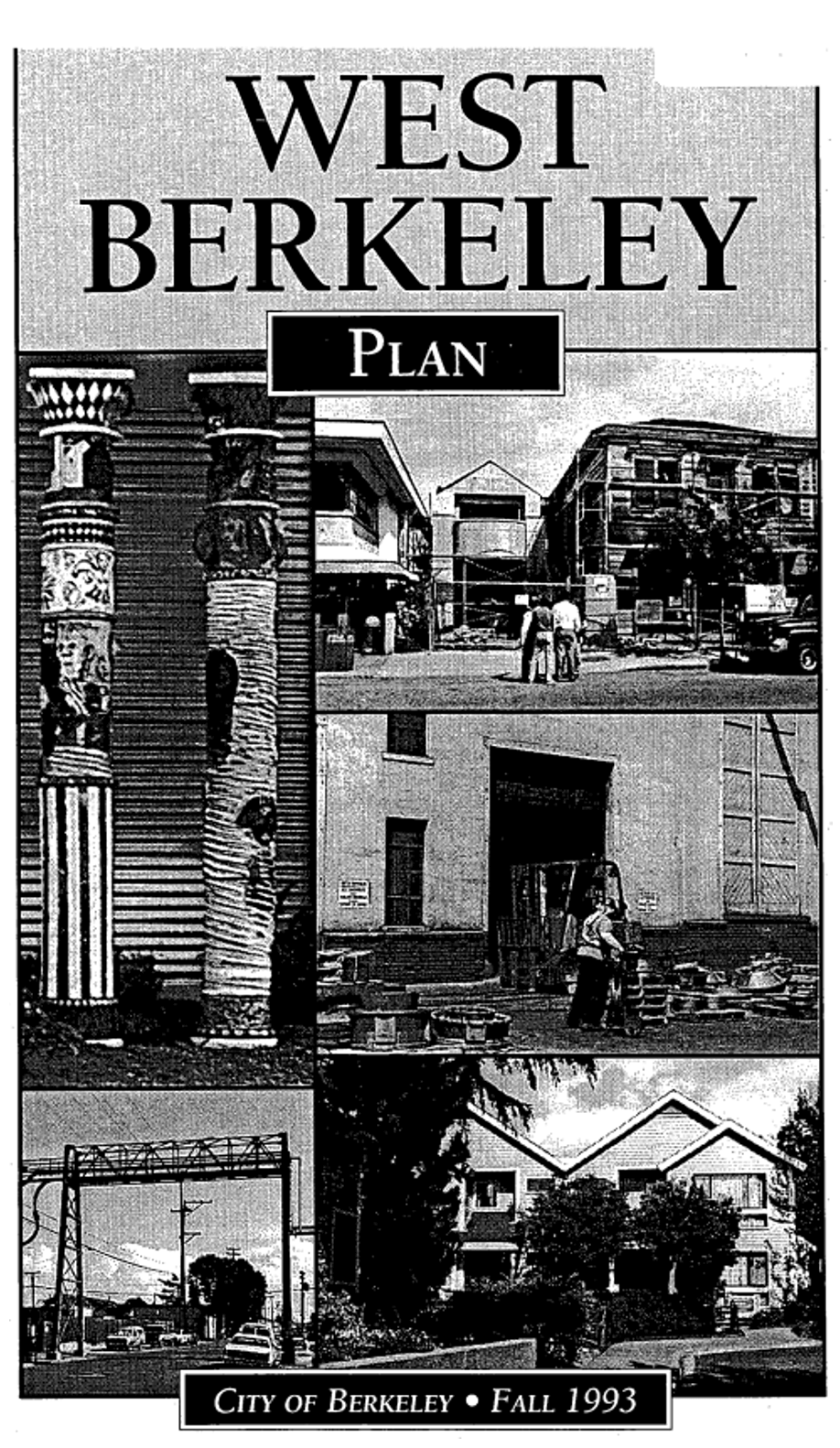

- Section B. Change of Use from Manufacturing or Industrial Uses: One unique aspect of the West Berkeley Area Plan is its restrictions on changes of uses from manufacturing or industrial activities. The plan mandates that only 25 percent of a manufacturing or wholesaling building’s square footage can be converted to other uses without a Use Permit.

- The initial Area Plan included a full Environmental Impact Report, certifying the plan for CEQA compliance and paving a path for streamlining of future development applications complying with the plan standards.

View this Case Study >

View this Case Study >The City of Brentwood created the Priority Area 1 Specific Plan in 2018. The area covered by the plan includes a 260-acre shovel-ready site dedicated to life science, technology, and light industrial development. This area, centered around the planned Brentwood BART station, is being marketed as the Innovation Center At Brentwood. The City has already leveraged the specific plan to begin $24 million of investments in public infrastructure, including a $9 million extension of Sand Creek Road. More information about this project and the associated master plan are available on the City of Brentwood’s website.

TOOL 2

District-Based Funding Mechanisms

District-based funding mechanisms are the only local funding source beyond a city’s General fund that can provide stable ongoing funding sources for infrastructure and/or place making investments. While there are a variety of options in California state law to establish district-based funding mechanisms, this toolkit focuses on two: Community Facilities Districts and Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts. These two tools can both pay for infrastructure costs that benefit multiple properties within a district and use annual revenue streams. In contrast to development impact fees, which are a one-time fee and have unpredictable timing, these district-based funding tools use ongoing levies or tax assessments to fund improvements. The predictability associated with the levies, taxes, or tax increment provides greater certainty that infrastructure investments will be made in a timely manner which can serve as an incentive for additional private sector investment in the area.

Because there are many different types of district funding mechanisms available to communities, local governments have the flexibility to choose the best tool for their context. These mechanisms can also be layered with other planning and finance tools, such as area plans, economic development zones, or development agreements.

Though there are many varieties of district-based funding mechanisms, these all rely on one of two funding sources. The first source is a levy or assessment that is paid by district participants in addition to property taxes. State law dictates specific procedures for district formation and sets forth the basis for establishing assessment/levy levels depending on the district type. The second funding source is tax increment, which works by establishing a “base year” for property tax revenue within the district. As property values, and thus taxes increase in subsequent years, the local government continues to receive property tax revenue equal to the revenue level of the “base year.” A percentage of the additional, or “incremental” revenue is deposited into a separate account, which is used to fund projects within the district. This tool focuses on the two district funding mechanisms that are the best options for industrial districts: Community Facilities Districts and Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts

- Community Facilities Districts (also called Mello-Roos Community Facilities Districts, or CFDs) work by imposing a special levy—on top of existing property taxes—on property owners within a designated area.

- Levy amounts can be imposed based on each property’s land area, building square footage, or varied by land use.

- CFDs can be used to pay for infrastructure investments—such as streets, water, sewer, or utilities— as well as services such as schools, parks, or police

- Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts (EIFDs) are a type of tax-increment financing (TIF) district that were created by the California State Legislature in 2014. EIFDs can encourage private investment within the district by reassuring property owners that some of their property taxes will be spent to upgrade facilities in the district, and that they will not pay any more in property taxes than they would have without the EIFD in place. EIFDs can be used on any property type, and can be used a wide variety of expenditures related to the district. Possible uses include brownfield remediation; water or sewer infrastructure; roads and bridges; or other transportation improvements.

- Climate Resilience Districts are a new tool formulated in 2022 as a subset of EIFDs. These districts function in the same way as other EIFDs, but their funds must be used to address climate resilience needs, such as sea level rise, extreme heat, extreme cold, wildfire risk, drought, or flooding risk. This new tool provides local jurisdictions with the opportunity to form an EIFD specifically to address climate resilience needs.

- Community Facilities Districts (also called Mello-Roos Community Facilities Districts, or CFDs) work by imposing a special levy—on top of existing property taxes—on property owners within a designated area.

District-based funding mechanisms can be used to provide amenities and infrastructure to support new industrial investment in contexts where market demand is strong or property values are expected to rise. Which tool a jurisdiction uses should be carefully chosen based on the political and financial implications of each. Here are some key differences to consider:

- Formation Requirements:

- Formation of a CFD requires the consent of either two-thirds of property owners or, in districts with 12 or more registered voters, at least two-thirds of registered voters. This makes political implications an important aspect of district formation, and makes it more attractive to create a CFD when the total number of property owners is smaller.

- In contrast, formation of an EIFD does not require property owner consent (though property owners can protest after the district is created.

- However, formation of an EIFD is also a political process, because other taxing entities, such as the school district and the county government, also get a share of the increment and have to agree to the EIFD’s creation.

- Municipal Finance Implications:

- Because a CFD institutes an additional “special tax,” on top of existing property taxes, it does not have an impact on a local government’s revenue.

- In contrast, an EIFD puts a cap on the property tax that a local government will receive to its General Fund from properties in the district—diverting some portion of the “incremental” revenue above that cap to the district’s separate account.

- Because the EIFD relies on the tax “increment” to generate revenue, the amount of revenue raised from the EIFD may be less predictable.

Case Study #1 – Gateway Industrial District CFD, Oakland, CA

The City of Oakland’s Gateway Industrial District is a 160-acre area created out of the former Oakland Army Base. It is adjacent to other key components of the City’s industrial ecosystem, such as the Port of Oakland and the West Oakland industrial area. The community facilities district was created in 2015 to provide funding for the maintenance of roads and infrastructure within the district. The tax for the community facilities district was set to $16,046 per acre (or $0.37 per square foot) in the 2015-16 fiscal year, and increases annually according to an inflation index. This funding is applied to maintenance, rehabilitation, and public improvements within the district, including: streets, curbs, landscaping, sewer, storm drains, bio-swales, traffic signals, and fencing.

What to Look At

- Normally, creating CFDs requires consent of two-thirds of property owners (or registered voters) in the district. However, at the time of adoption of the CFD, the City of Oakland owned all parcels within the district. This meant that only one property owner, the City of Oakland, had to consent to the creation of the district. Of course, the City is exempt from paying the special tax that comprises the Community Facilities District’s maintenance fund. However, as properties are disposed, either via sale or ground lease, the new property owners & ground lessees take on the burden of payment for this tax.

- The Lease/Disposition and Development Agreement between the City of Oakland and California Waste Solutions provides an example of how leasing and sale of property within the district is being used to increase the funding pool for the CFD. Section 6.3.2 of the agreement provides notice to the developer of the terms and conditions of the CFD.

Because EIFDs are a relatively new district funding mechanism, and they can be politically complicated to create, no Bay Area communities have, as of 2023, established an EIFD for a primarily industrial area. However, the City of Napa established an EIFD in 2022 for a mixed-use district that includes some industrial properties. In addition, many other EIFDs have been created, or are under consideration currently around the state. The Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) is a great resource with more details on these, as well as CFDs and other value-capture based funding mechanisms that could be applied in industrial areas.

TOOL 3

Economic Development Zones

Economic Development Zones can be used to incentivize business investment in a location where land use policy alone may not be sufficient to attract new industrial activity. This tool can be implemented more quickly, and with less complicated policy processes than an extended initiative such as an area or specific plan. When used in conjunction with a target industry strategy that considers a community’s unique strengths within the regional economy, this can be a powerful tool for advancing industrial development in areas that need a business attraction boost. If used effectively, an economic development zone could help incentivize investment in industrial areas from industries that match a community’s competitive advantages within the region. Then, as macroeconomic conditions, and a community’s competitive advantages, change, incentives and target industries can be updated to help the community transition its industrial land uses.

The Economic Development Zone concept, as used in this toolkit, has the following characteristics:

- A defined geographic area in which one or more economic incentives are available to developers and/or businesses.

- Examples of these incentives could include property tax abatement incentives; impact fee or user fee reductions; expedited permitting; rebates and cost reimbursements; loans; business license fee exemptions; or public investments to support new business development, such as infrastructure or job training contributions.

- Incentive offerings are tied to a broader target industry strategy for the community’s industrial lands, based on the community’s competitive advantages and its opportunities within the regional economy.

- Businesses must meet certain eligibility criteria to receive incentives.

- Criteria could include length of lease; job and wage levels; investment amounts to be made by the business or developer; and/or meeting certain business size qualifications.

However, the concept of an “economic development zone” is not formally defined, and has no legal definition in the state of California. This particular tool is patterned off of the City of Dublin’s economic development zone, and similar types of zones and investment areas that have been used around the country to incentivize industrial development previously. Two local East Bay examples illustrate how this term can be used in conflicting ways:

- The City of Dublin’s Fallon Road Economic Development Zone matches the characteristics outlined above. Please see Case Study #1 below.

- The City of Pleasanton’s Johnson Drive Economic Development Zone has a different focus: using sales tax revenue and transportation impact fees to fund transportation investments for the area.

The innovation of Dublin’s economic development zone is that it takes existing incentives—enabled by State legislation—and aggregates them in a specially designated area.

- Economic development zones are best used in the context of greenfield development, where an area has unique advantages for industrial development, but does not yet have an economic nucleus for industrial activity.

- While “economic development zones” are not a legally-defined concept, they are still subject to California State law related to economic development incentives, because each of their individual incentives are enabled by that legislation. As such, any expenditure or loss of public revenue greater than $100,000 must meet the requirements of AB 562. This involves the following compliance steps:

- Prior to granting the subsidy, hold a public hearing, and publish a subsidy report.

- Detailing the beneficiary; start and end date; dollar amount; public purposes; and job implications of the subsidy.

- After granting the subsidy, prepare an updated subsidy report & public hearing.

- Analyze net tax revenue resulting from the subsidy.

- Analyze net number of jobs created by the subsidy.

- Economic development zones should be used in conjunction with a target industry strategy that properly accounts for a community’s competitive advantages in the context of the regional industrial ecosystem. This requires identifying how the local economy fits into the larger regional economy, and focusing on how new economic development can be complementary to that occurring in nearby areas.

- For more on this concept, please refer to the Regional Ecosystem Collaboration portion of this toolkit.

- Prior to granting the subsidy, hold a public hearing, and publish a subsidy report.

Case Study #1 –

Fallon Road Economic Development Zone, Dublin, CA

The City of Dublin established an Economic Development Zone in 2021 to incentivize investment in a 73-acre greenfield area between Fallon Road and I-580. The City is seeking to attract life science, advanced manufacturing, green tech, automation, or other startup activity by providing a suite of incentives within the zone. Incentives include property tax sharing, streamlined development review, fee reimbursement, and a green construction incentive.

Source: City of Dublin, 2021.

What to Look At

- EDZ Fact Sheet: City Programs

-

- The City of Dublin is offering EDZ investors a suite of potential incentives, including up to 50 percent of City property taxes for five to ten years; development fee deferral; and a 20 percent discount on building permit and inspection fees.

- Take note of the eligibility requirements for each of the incentives—they are marketed to either property owners or ground leaseholders. In this way, the incentive can be used to encourage development activity, or business leases; business occupants of the properties can use the incentives for their tenant improvement expenses or purchases of new equipment. Businesses also must qualify as one of the City’s target industries for the zone.

- EDZ Fact Sheet: Marketing of State/Federal Financing Programs

- The City is also offering staff support to businesses who wish to pursue state or federal incentive programs. If utilized, this could enable the City to secure additional subsidies for local businesses without directly reducing City revenue.

-

TOOL 4

Development Agreements

Development agreements represent a public private partnership that includes a single large property owner and a city. This agreement can be used in many of the same ways, and with many of the same benefits, as district-based tools like area or specific plans. By establishing standards, approval process, and development fee structures for a large parcel or cluster of properties, development agreements can be used to streamline future development and facilitate flexibility for businesses subject to the agreement. This is because development agreements can be used to establish standards for future developments—giving businesses the flexibility to adapt their practices or structures as long as they conform to those standards. These types of agreements also often include community benefit requirements or financial agreements that can help compensate for long-term infrastructure requirements or other public services. By negotiating these requirements up front, cities and property owners can identify a financial structure that works for both parties and enable long-term investment.

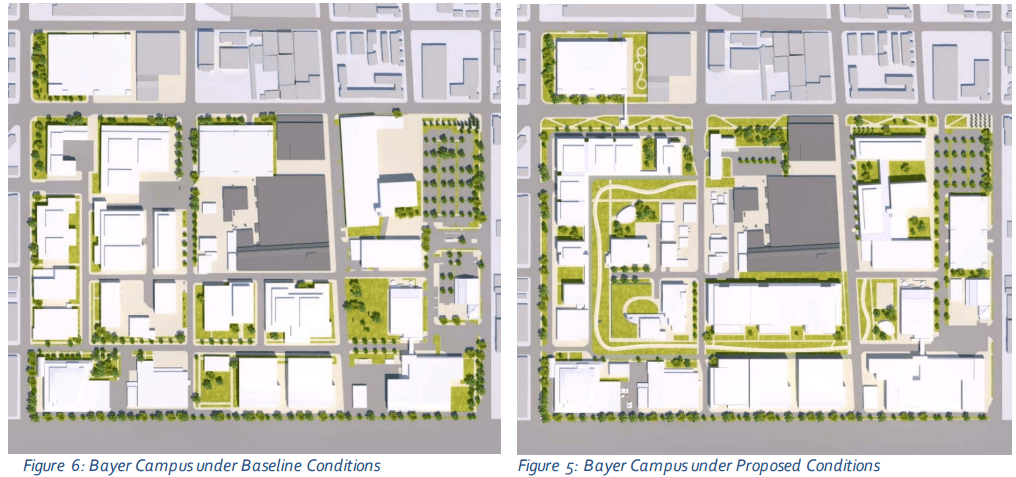

The Harbor Bay Business Park is an example in which an agreement was entered with a group of three entities, which have changed over time as properties exchanged hands; however, it is also common for development agreements to be used to facilitate the expansion of a single business over time. For example, the City of Berkeley recently renewed an agreement with Bayer, in which the company agreed to pay $33 million in community benefits over time, in exchanged for increased height allowances and streamlined approvals. Funds from the new agreement are being used to support education partnerships, community resiliency, affordable housing, childcare, and the arts.

Development agreements are formal agreements between a local government and a property developer regarding the allowed uses, density, height, and public land designations on that property. The agreement must also specify a duration, and may include additional provisions for financing of public facilities. While development agreements must be compliant with a community’s general plan and any relevant specific plan, the negotiable nature of development agreements makes them very flexible for achieving both City and property owner goals. For example, a development agreement for Harbor Bay Business Park in Alameda has been used over the course of 30 years to provide funding for roads, a bike and pedestrian path, landscaping, a public shuttle, and other neighborhood benefits. In exchange businesses have been able to use the site flexibility and maintain the upkeep of their community.

The Harbor Bay Business Park is an example in which an agreement was entered with a group of three entities, which have changed over time as properties exchanged hands; however, it is also common for development agreements to be used to facilitate the expansion of a single business over time. For example, the City of Berkeley recently renewed an agreement with Bayer, in which the company agreed to pay $33 million in community benefits over time, in exchanged for increased height allowances and streamlined approvals. Funds from the new agreement are being used to support education partnerships, community resiliency, affordable housing, childcare, and the arts.[1]

[1] City of Berkeley. (2021). Amended and Restated Development Agreement with Bayer Healthcare LLC.

Development Agreements, if properly structured, can lead to decades of future investment in a concentrated area within the community. Communities should consider the following recommendations when implementing development agreements for large sites:

- Community benefit negotiations become very important in cases where there is strong market demand for new development, as this market demand provides a community with more leverage for securing community benefits in exchange for development rights.

- Cities should take care to ensure that community benefit requirements or other financial agreements are sufficient to offset any potential impacts of development, but not so onerous as to prevent development from occurring if market conditions change.

- Overall, it is best to emphasize flexibility and identify fair terms for both parties, especially since these agreements are likely to cover multiple real estate market cycles.

- Development Agreements should be used to establish a precedent for environmental review and self-sustaining methods (such as transportation funds) to mitigate possible environmental impacts of future developments that would be pursued under the terms of the agreement. See the Harbor View case study below for an example of how these processes can be used to enable CEQA exemptions.

- Community benefit negotiations become very important in cases where there is strong market demand for new development, as this market demand provides a community with more leverage for securing community benefits in exchange for development rights.

Case Study #1 – Bayer-Berkeley Development Agreement, Berkeley, CA

In 1992, the City of Berkeley formed an agreement with Bayer Healthcare (formerly Miles Inc.) regarding the buildout of the company’s West Berkeley campus. This initial agreement governed building sizes, uses, and distributions. In 2021, the City renewed this initial agreement for another 30 year term, granting additional development rights and defining permitted uses, density, height for new developments carried out by Bayer within the project site. The agreement also outlines public benefit contributions to be provided by Bayer, as described in the tool details above.

What to Look At

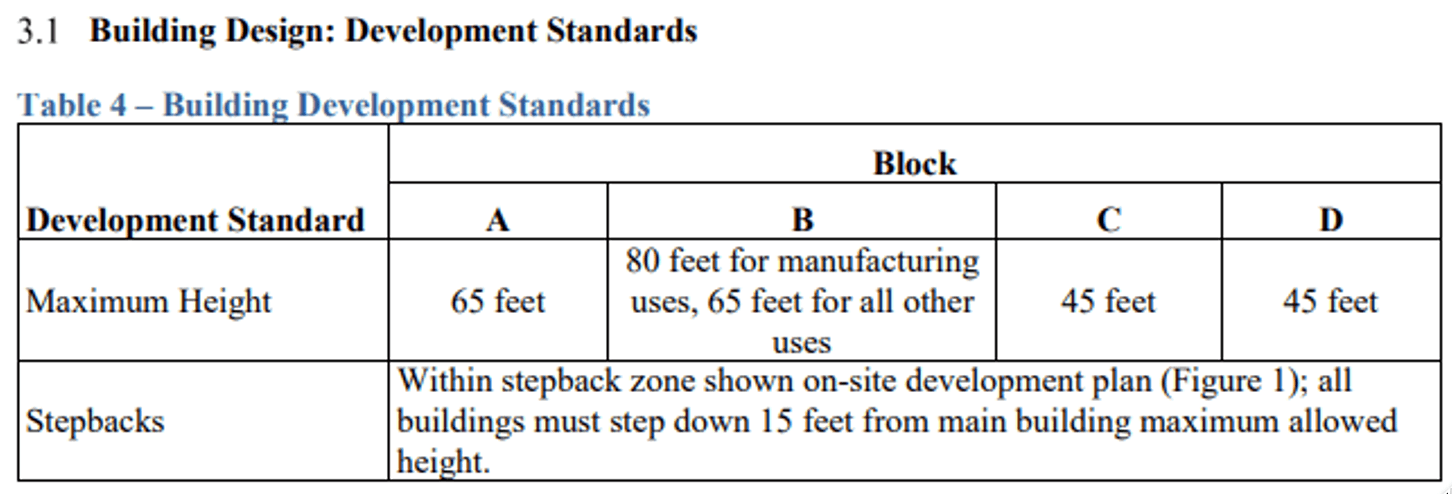

- Exhibit C (Starting on page 39) provides site development standards and design guidelines for the campus. This exhibit outlines the types of permits and design review needed for each type of development activity on the site. For example, construction of buildings of less than 40,000 square feet require a zoning certificate and only staff-level review. Development standards are outlined for each block:

Source: City of Berkeley, 2021 - Exhibit D (starting on page 73) outlines community benefit investments to be made by Bayer over the 30-year period, and describes how each of the funds will be allocated. It also formalizes agreements for impact fees. It also establishes standards and guidelines specifying how each community benefit will be administered.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Case Study #2 –

Harbor Bay Business Park, Alameda, CA

In 1989, the City of Alameda created an agreement with three Harbor Bay entities to provide for public service provision and infrastructure investments associated with developments in the Harbor Bay area. In line with this agreement, the Harbor Bay Business Park’s developers built streets, sewers, landscaping, a ferry terminal, a public park, and a new commuter shuttle for the area. In exchange for these investments, the City of Alameda provided development rights for the new business park and specified standards for density, height, and size within the project area. According to local stakeholders, this business district has thrived because the development agreement allowed for flexible zoning and use cases, and preserved industrial lands in close proximity to other business locations.

What to Look At

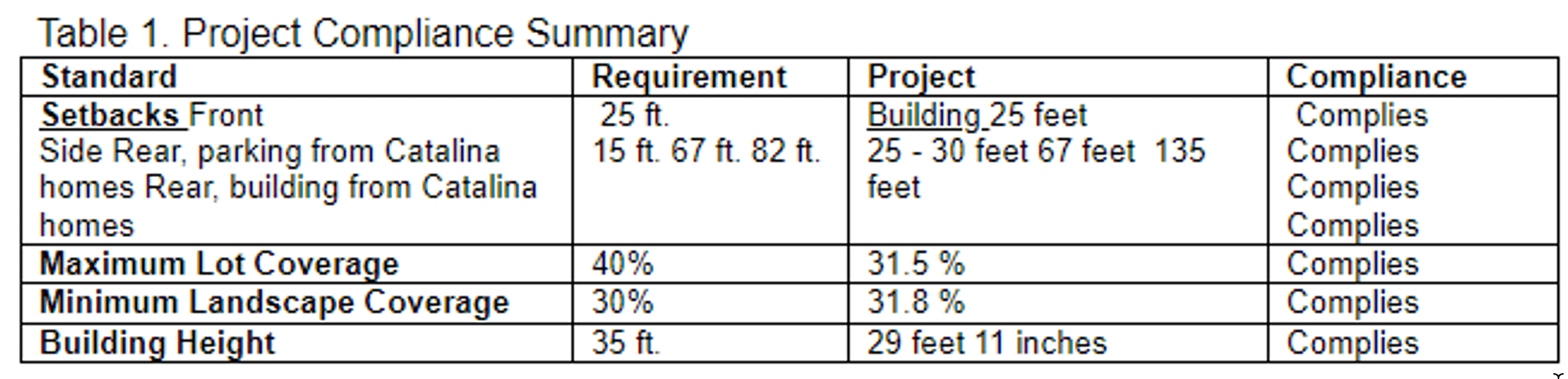

- Example Development Plan and Design Review, 2018:

-

- The Planning Board report from this 2018 hearing provides an example of the benefits of development agreements for streamlining approvals when a proposal complies with the terms of the development agreement. City Staff’s analysis of the proposal and site plan describes how the new project would pay into the existing funding structures in the Development Agreement and comply with the site’s development standards.

- The environmental review section of the staff report also describes how the project met the terms of a categorical exemption from CEQA as an infill development, per Section 15332, Class 32[2]. This qualification was in part due to the existence of the Development Agreement, with a completed EIR and mitigation measures for traffic impacts. In this case, the project would be paying into the Harbor Bay Business Park Traffic Improvement Fund, which is used to cover transportation improvements and mitigate traffic impacts for the area.

- The Planning Board report from this 2018 hearing provides an example of the benefits of development agreements for streamlining approvals when a proposal complies with the terms of the development agreement. City Staff’s analysis of the proposal and site plan describes how the new project would pay into the existing funding structures in the Development Agreement and comply with the site’s development standards.

- Renewal of the Development Agreement: The background section of this Planning Board update provides an overview of the history of ownership and development agreement management over time in the Harbor Bay business park. This history illustrates the flexibility of development agreements to continue.

-

[2] The City of Los Angeles has developed a primer on this exemption.